A short guide to Iliotibial Band pain (ITBS)

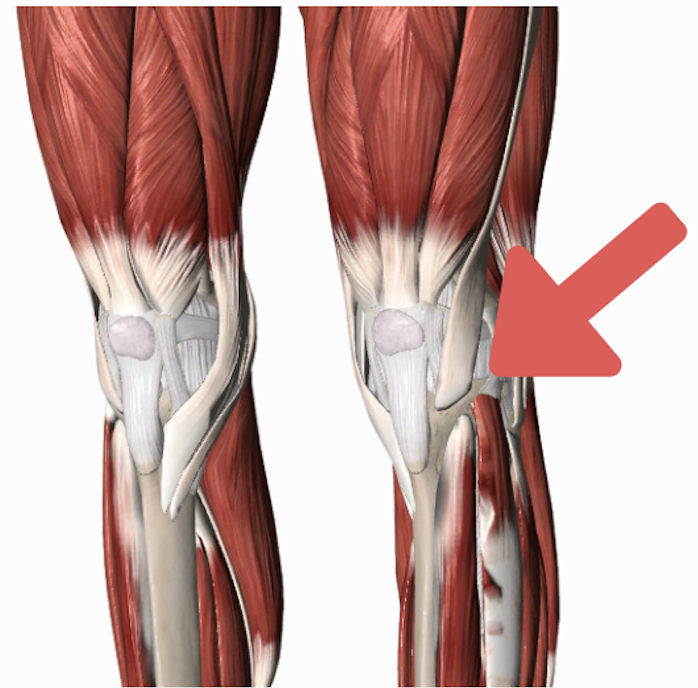

Iliotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS) is a common cause of pain among runners, affecting the iliotibial band (ITB) located anywhere along its length but usually at the outer knee. It often is a result of too much too soon in relation to running, cycling or rowing – when the knee moves in and out of bending/extending really quickly.

What causes ITB pain?

Causes of ITBS have been extensively researched but are mostly inconclusive, since overuse injuries usually have more than just one contributing factor. Here’s what we know (or more accurately, don’t know):

Friction between the ITB and the outer knee

- Friction between the ITB and the lateral femoral condyle during knee flexion-extension activities

- This friction can create an impingement zone during certain phases of running, such as the heel strike or early stance phase

- Compression of the fat pad near the ITB insertion may also contribute to the development of symptoms

Muscle Strength

- The relationship between muscle strength or endurance and ITBS remains inconclusive

- Isometric muscle strength testing may not accurately translate to the specific muscle motion and usage required during running

- However, maintaining pelvis stability, possibly through the involvement of muscles such as the gluteus maximus, tensor fasciae latae (TFL), and gluteus medius, could be related to ITBS prevention

Pelvic Position and Load Changes

- The influence of pelvic position on ITBS has not been extensively studied, but there is weak evidence suggesting that frontal plane pelvic control may be related to the condition

- Load changes during running can also affect ITBS, with forefoot running placing more load on the lower leg, foot, and calf, while heel striking results in greater braking forces through the knee and quadriceps

Movement Patterns and Compensatory Mechanisms

- Analyzing running mechanics becomes challenging when trying to determine if observed movement patterns are a result of pain, preexisting conditions, or compensatory strategies aimed at reducing pain

- This complexity makes it difficult to establish causal relationships between movement patterns and ITBS

Stretching and Release Techniques

- Stretching exercises can target the ITB, primarily showing changes at the proximal end where the TFL muscle attaches

- The stiffness of the ITB itself does not significantly change with stretching

- Symptomatic patients may exhibit decreased ITB stiffness, which tends to increase after intervention while pain decreases and function improves

- The stiffness of connective tissues, including the ITB, is believed to contribute to elastic energy storage, crucial for running

Knee and Foot Position

- While impingement at 30 degrees of knee flexion is considered insufficient to determine the presence of ITBS, studies have not confirmed the theory that rearfoot eversion (tibial internal rotation) is directly related to ITBS

- Evaluating foot posture and relying on visual observation alone are not reliable indicators of ITBS

Treatment of ITBS Pain

That won’t give you an answer as to WHY you have ITB pain, however, it should be helpful to know that your treatment plan doesn’t have to be overly fancy. Often you can do self management techniques like stretching to reduce pain, and then have a progress strengthening plan in place, while slowly managing your load!

Both stretching and strength training have shown similar improvements in pain associated with ITBS, suggesting that incorporating strengthening exercises can provide additional benefits beyond pain relief. Foam rolling has shown immediate pain reduction, but the long-term effects on function and performance remain uncertain.

Stretch and muscle release:

- Stretching your hip flexors may help as the TFL muscle attaches directly into the ITB

- You cannot actually stretch the ITB itself as it is a VERY strong band of connective tissue and you actually want it to be stiff while you run

- Try this hip flexor stretch

- Complete it daily in the morning and night.

Strengthen and exercise rehab:

- Work on your quad muscles, glutes and hamstrings – these will help manage the load as you do your activity

- Do these 4 exercises in a circuit, NOT pushing into your usual pain. Complete 20-30s of each exercise, twice.

- 30s quad deceleration exercise (to help absorb load while you run)

- 30s glute strengthening exercise

- 30s hamstring strength exercise

- 30s hip stabilization exercise

Complete on the injured side, but ALSO complete these on the uninjured side to make sure it is strong and stable for your recovery.

Load management and gradual progressions

- Ease off the aggravating activity – but don’t completely stop

- Complete in intervals of a slower pace (walking for example), then faster pace (running) without pushing into your pain

- For example, walk 2 mins, run 2mins, and complete for 10 minutes. Only progress if your pain is not aggravated for 24 hours

To stay on top of your running injuries, grab your copy of my FREE Everyday Running ebook – injury prevention tips and a mini program.

This is generic information so please take your own injury into account and see a health professional for medical advice!